Two Stories

from Tightrope: a PUNK NOIR Magazine series

A Job in New Orleans

by

Nils Gilbertson

I picked up the gun from an old man in a balcony apartment one block up from Bourbon Street. He smoked a joint and didn’t say much. Better that way, I thought. Jazz guitar, tuning up, reverberated from the whiskey bar downstairs.

I pressed the magazine release and fingered a nine-millimeter round. “Any suggestions for ditching the gun?”

The old man only grinned, his face like a weathered mask.

The bar downstairs was mostly empty. My only companions, beyond the bartender, were the jazz trio and a balding man tending to a double whiskey. Guitar rang and the drumbeat mimicked the rhythm of my chest. I double-checked the address, the instructions, and tried to forget the holstered piece underneath my coat. “Wild Turkey, rocks,” I said. I tried to escape into the music. Walking on a Tightrope by Percy Mayfield. A tightrope—I knew the feeling. A place where there was no standing upright; the only choice was which way to fall.

The bartender was pregnant and smiled at me as though I deserved it. After serving my drink, she went to the balding man a few seats down.

“Another one, darling?” she asked.

“Sure.”

“Double?”

“What the hell.” He sucked an ice cube from his drink as she fetched another. After she served it, he took a slurp of whiskey and made a gesture like a half-hearted prayer. “I love this town,” he said to the bartender. “My wife loves it even more.”

“And you came without her?” she asked.

He took another sip. “She passed. We’re here on our last trip together.” He gestured toward a small urn on the barstool next to him.

The bartender’s face curled downward. “I’m so sorry to hear it.”

“Thank you,” he slurred.

“When was it?”

“Four months ago.”

She poured him a glass of water without a word.

“She loved it here,” he said. “She loved the oysters, the cocktails. We came twice a year.”

“I’m so sorry.”

He stared at the ice, disappearing, in his glass.

The bartender served my drink, and I drank.

“Where you in from?” I asked him.

He looked at me. “San Francisco. You?”

“Great town,” I said. “Hell of a price tag, though.”

He grinned. “You ever hear of rent control?”

“Sure.”

“My wife and I pay $1,800 for our apartment in the Mission. Been there twenty years. You know how much the new couples moving in pay?”

I shrugged.

“Near five grand.” He chuckled. “A nice place, too. My wife used to say that they’d have to drag us out of there in body bags.” His smile disappeared, and he turned back to his drink.

“Well, I’m sorry.”

“I brought her ashes,” he said, placing his hand on the urn. “Our last trip together.”

“They staying here?”

“Sure,” he said. “Why not. She’s with me either way.” A red-cheeked, watery-eyed smile.

I finished my drink and stared at a fly on the wall and listened to the jazz trio play, each melody plucking my nerves like a guitar string. But even in the darkened barroom, there was light. In the corners and crevices, there was so much light it would blind you.

I paid my tab and wished the man good luck. His eyes, half closed. Tired. Too much to forget.

I walked a few blocks toward Jackson Square. The gates were locked, so I sat on a ledge and peered up at St. Louis Cathedral. It was quieter than Bourbon Street, the rhythms of night, piercing staccato of drunken revelry only a few blocks up, like sirens in the distance. The breeze like God’s whispers. Stained glass glowed, judging, yet loving. The gun heavy under my coat. Still, the light soothed me. Its glow, accompanied by the drink in my veins, insisted that all could be forgiven. All evil could be repurposed for good.

People crossed my path. Drunken groups of men and women, their merriment like little bursts of chaos. Then others who had long passed that stage, the joyous chaos devolved to an inescapable stalemate of addiction. A truce with the Devil in a burning field.

“My man,” I heard.

I looked up.

“You got a stem?”

“No, I’m sorry.”

He grunted and moved on.

I watched him go. As he went, others came. I bowed my head, but not for too long, because I didn’t want to miss any of them. The balding man—his dead wife—the bartender and her baby—anyone.

“I love them all,” I whispered. “I love everyone. Everything.”

Something in me cursed that it was a lie. I checked my watch. It was almost time. A dirty, goddamn lie.

The whiskey, I thought. It’s only the whiskey. The familiar poison breeding synthetic passions—passions I had been trained to feel—exaggerated by the glow of the stained glass, illuminating the cross so far upward that it strained my neck to look upon it.

So, I looked down.

When I did, my phone lit up. I didn’t read it.

Instead, I walked until I found water. Swells like goodness itself coming to wash away all I had done—all I hadn’t.

I imagined the balding man, standing at the water’s edge, sprinkling her ashes. I imagined everything after, too. His walk back to the hotel, the ride to the airport, the lines, the flight. Only to return home without her.

I imagined crossing the river on a tightrope. The inevitable fall.

I tossed the gun and the phone into the Mississippi. They sank in the inky water. I turned back to the lights of the French Quarter—the sounds, the revelry—and returned to everything I had ever loved.

Nils Gilbertson (www.nilsgilbertson.com) is a writer and attorney living in Texas. His short fiction has appeared in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, Rock and a Hard Place, Mystery Magazine, Cowboy Jamboree, and others. His work has also been published in various anthologies, including Mickey Finn: 21st Century Noir and Prohibition Peepers. Nils’s story “Lovely and Useless Things” was selected to appear in both The Best American Mystery and Suspense 2024 and The Best Mystery Stories of the Year: 2024. His story “Washed Up” was named a Distinguished Story in The Best American Mystery and Suspense 2022.

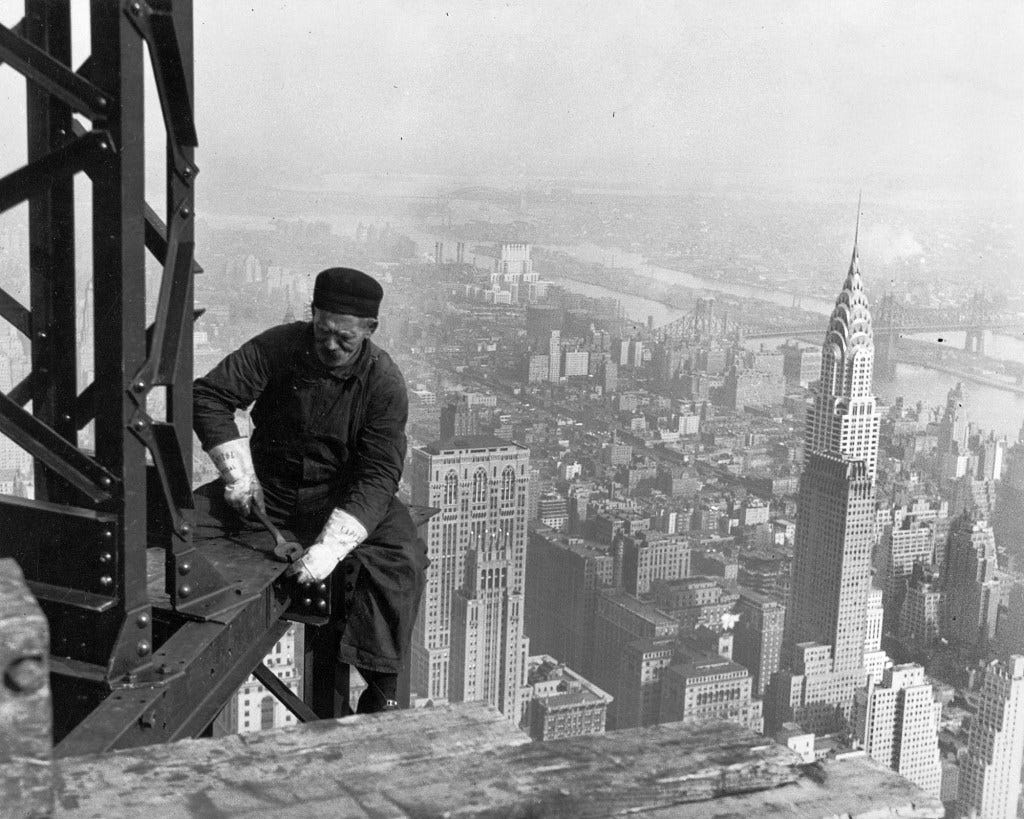

“Empire”

by

Frank Vatel

“…for Jacob Nowak, who was given the promise of eternal life in Baptism…”

Whenever a spider-man goes home to the lord, there’s always a prayer next day. Priest comes up the main shaft about seven-thirty and we all circle around.

First time it happened, a kid named Tedesco, we paid our respects proper and solemn. Thinking it was a fluke he slipped on that scaffold. Thinking there wouldn’t be no more.

Now it’s five and counting. Ozzy says the novelty’s worn off.

As the priest talks, I see a man wandering the platform. Tall and raw-boned in fresh coveralls. The greenhorn, I think.

Sure enough. After the circle breaks, Ozzy brings him over.

“This here’s Anson,” he says. “Starrett’s people sent him. He’ll be our fourth till Carmine gets well.”

He introduces Fran, then turns to me. “This is my brother Zeke. You’ll be working with him, mostly. Don’t expect much conversation. He’s dumb as a post.”

The greenhorn stares me down. Lots of folk stare at me, but his eyes are different. Strange, unblinking. Reminds me of something unhappy, but I can’t place it.

“Where you cook before this?” Fran asks.

“My old man’s crew,” says the greenhorn. “He’s a contractor up Woodside.”

Fran trades a glance with Ozzy. “Any high steel?” he asks.

“Park Row building. Some maintenance.”

This is good enough for Ozzy, who’s under pressure and wants the greenhorn set up fast. He takes him round to the stove, leaving Fran and me with our coffee.

“What do you make of him?” Fran asks.

I purse my lips and shrug.

Fran don’t mind I’m dumb. He’s Italian, and Ozzy says nothing stops their kind from talking, least of all a fella who can’t answer.

“You know he’s lying about Park Row,” Fran says. “It ain’t had repairs since twenty-two.”

He lights a smoke and studies my chagrin, snorting in amusement.

“Don’t fret, Zeke. We all gotta start somewhere.”

***

The first one nearly clips my leg. It’s all I can do to scoop it on the bounce so it don’t burn through the platform.

Ozzy always says a real man don’t apologize. I reckon the greenhorn concurs. He’s already back at the fire, cooking the next one.

I deliver the piece, expecting Ozzy or Fran to mention what happened. But they’re busy securing the beam. Fran extracts the hot rivet from my bucket and presents it to Ozzy, who nods his approval and fires up the gun.

Maybe it’s for the best they didn’t see. No reason for a greenhorn to catch trouble for something that’s my fault. Catcher’s job is to bring the cook along, teach him to throw—slow and easy, with a nice arc. But I can’t teach nobody.

Back at the stove, it’s more of the same. The second and third ones come at me just like the first—low and fast.

The fourth one tags my shoe and skips off the platform. The stink of branded leather reaches my nose.

This time, Fran speaks up.

“What’s say we keep it waist-level, Anson? Give old Zeke a fighting chance.”

Fran whispers something to my brother, who sets down his tool and watches us for the first time. This distracts me just long enough. When I turn around, there ain’t no time to react. The incoming rivet puts me square on my ass.

Draped over a length of steel and miles of air, I freeze. The greenhorn’s stare burns through me like a flame, same as before. Only now it’s floating above a murderer’s grin.

Suddenly it all comes back to me. Ozzy and me, the farm, the bloodhounds. Daddy laying into those dumb creatures with boots and belts, wringing their necks, eyes glowing with a wicked pleasure I hoped never to see again.

But I was seeing it now.

Fran knows about my nerves. He rushes over and slaps me gentle on the face. Then he props me up northeast so I can see my favorite tower. Already I feel calmer.

The Chrysler looks nice this time of day—the crown and spire picking up the sun, winking at us from Lexington. We met Fran and Carmine on that build. Thirty-two months. No deaths.

This one’s going up a lot faster. Ozzy says it’s gotta be that way—there won’t be no tenants in thirty-two months. Just breadlines and nervous breakdowns.

***

It’s almost lunchtime, so we’re winding down. Ozzy supervises the greenhorn as he puts out the fire.

“You like this work, Anson?”

“Fourteen a day ain’t nothing to sniff at.”

“No, it ain’t,” Ozzy says, lighting a smoke and turning to admire the views. “But that ain’t the best part.”

The greenhorn sets down his tongs. “What’s the best part?”

“You got lunch?”

“I saw a commissary down there.”

Ozzy shakes his head, jabbing the cigarette toward Fran and me. “These two knuckleheads can fetch our sandwiches. Meantime, I’ll show you how we take our coffee and smokes up here. You ain’t seen nothing like it, I promise.”

He offers a cigarette. After thinking a moment, the greenhorn takes it.

Across the platform, another team is finishing up. Ozzy stuffs two bills in Fran’s pocket. “Take Freddy’s gang with you. Tell him lunch is on me.”

He pats my cheek. Fran lays an arm on my shoulder, leading me away.

***

Going down in the lift, everybody’s talking up the Canzoneri fight. Dooley says he’s got a sawbuck on Kid Chocolate, but nobody believes him.

Curiosity gets the better of me and I stick my head out the window.

There they are. Ozzy and the greenhorn, high above us on a beam. Watching the heavens. Getting smaller and smaller as we drop. A line and two dots, suspended in light.

The wind riffles my hair and I feel all my agitation leaking out. I’m sleepy now.

My eyes shut.

Then I hear it. A whistle past my ear, like God blowing out a flame.

My eyes open.

A line. One dot.

Frank Vatel is a writer and freelance illustrator whose work has appeared in Punk Noir Magazine, All Due Respect, Bristol Noir, and Reckon Review. He spends far too much time discussing crime fiction and old movies on social media and is currently penning a noir novel set during the Depression. He lives with his wife in a rapidly deteriorating apartment in Chicago. He can be found on X (@Vatel1675) and Bluesky (@frankvatel312.bsky.social).

Really cool stories, thanks for sharing!